Palestinians in the Street: Our Concern, Not Our Concern

This blog post will hopefully be the first of many Arabic-English translations. As a Lebanese-Syrian in the US, I experience some of my greatest joys watching friends and comrades throughout the Arab world (and its diasporas) write, organize, and protest for our liberation, most recently with Lebanon’s ongoing October Revolution. Based on this enthusiasm and solidarity, I hope to translate some of these writings and share with English-reading audiences.

It’s fitting that my first translation is an article by Sarah Kaddoura, a friend who’s been organizing for years around Palestine, intersectional feminism, mental health, and much else. I was lucky enough to meet her in-person when I first visited Beirut in 2015, and I’ve always remained impressed by her principles, talent as an educator, and fearlessness. She writes and translates at her blog Suhmatiya. Below is her latest entry, reflecting on the position of Palestinians in Lebanon’s uprising.

Today was exhausting unlike all other days, though it was the most quiet. Nobody pulled out a knife on me, I didn’t chase a harasser to tell him to get away from “our street,” I didn’t run from one street to another avoiding detention, and I didn’t stay in Riad El-Solh Square for more than 10 hours. I decided to return home at 8:00 PM. My mom was very happy with this news on Whatsapp. Since the morning, she messaged me several times that she doesn’t want to see any photos of me getting detained. This is their country, these are their protests, “it’s not our concern.”

If I get detained, the news will mention my nationality, exactly like the headlines about the resort in Tyre purposefully mentioning the tresspassers’ Lebanese and Palestinian nationalities.1 It doesn’t stop there, since I know what happens to refugees after they’re detained. While a Lebanese that gets arrested is beaten, a gay Syrian is punished for spreading his vice in “their” country. The Palestinian arrested for hash spends three years in Roumieh Prison without a trial instead of two days at the police station.

I did not return home early for my mom: these days I am practicing a personal revolution against my family. I returned because I am tired. My body is fatigued from seven days of walking, running, screaming, and eating cookies for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. My Palestinian friend waits for me to take a taxi to ensure I will return home safely. I get inside and there’s a young man and woman both holding Lebanese flags. She says to him, “I ran out of patience while waiting for you,” and I ask her if she’s Palestinian because of her accent. She says yes, he smiles adding, “Me too,” and we chat a little. She’s from Beirut, and she’s originally from Acre, but she doesn’t know what camp in Lebanon she’s from. When we refugees are asked “Where are you from?” the answer has three parts: where do we live in Lebanon, where in Palestine did we (the Nakba generation) come from, and which camp did our first generations live in. I am from Sidon, my origin is from Suhmata, and my family lived in the Rashidieh Camp in Tyre.

I was surprised when the young woman did not know the camp that her family had lived in. But she is Palestinian, hodling the Lebanese flag, going to the demonstrations daily, just like my friends that were with us a few months ago during the refugee camps’ mobilization, demanding Palestinians’ civil rights. We see each other today in Martyrs’ Square and Riad El-Solh, exchange smiles, and say to the other, “Hey Palestinian, what are you doing here?!” What the Lebanese silence over the refugee camps’ mobilizations had frustrated, our friends’ loving and supportive chants from Riad El-Solh had revived. We love the streets despite our better judgment.

I go down to the street with enthusiasm and anxiety. I feel alienated inside most political groups, and I feel the need to mention my identity to see facial expressions and expect a change in the discourse. So that I can feel that I’m not erased within the mobilization that replaced the sectarian parties’ flags with Lebanon’s, though a gained achievement. I still don’t feel truly a part of this. How do I justify my demonstrating on the street without escape to cliches that I don’t believe? I do not love Lebanon today, I do not love this Lebanon, I do not feel belonging, and the feeling is mutual.

For me, nationalism is direct and indirect violence towards me and all other refugees and migrants. I hear songs like “Tell Them You’re Lebanese,”2 and I get a little nauseous because I really do not understand what merits this pride. I am not able to wrap my head with the flag like the Palestinian woman from the taxi, and I am not able to forget the camp where my parents and grandparents lived, or the camp that they were moved from and to another like cattle. Or the camp where my grandfather was killed at its checkpoint. I am not able to forget because it is not allowed for me. When I give my identity card, the blue refugee card, to a worker requesting it for a specific service, they ask me if this is a real ID… 72 years in this country you jackass, you’ve never encountered a Palestinian ID? How do I forget?

I protest knowing this identity will increase my misfortune tenfold if I am detained. If I am asked about what I’m doing, I will not be able to lie. I will not say “I love Lebanon, my second country.” I would like to love Lebanon to escape these feelings. I am tired when I think about my choices of migration and asylum that press upon me. Which country receives us without ferreting into our political opinions, and which country is spared from my tongue? Which country receives me and everyone I love, where I don’t enter a new cycle of depression and anxiety for years, so that my feelings of alienation don’t multiply?

I want to love Lebanon so that my existence becomes less tiresome. I go to the street for my civil rights. I protest so that I don’t have to change my accent in Achrafieh when I talk about politics. I protest so that Sidon doesn’t remain the only city where I can feel safe with an outbreak of security incidents (more than half of the population there are refugees). I protest for a better Lebanon, one that I could love because refugees, queer people, trans people, and migrant workers could feel safe. So that fear does not rule over us when we walk by the Gendarmerie and one of its men harass us. So that there is not another racist apartheid wall surrounding a refugee camp. So that we don’t lose my childhood home when my mother passes away. So that I don’t fear the hospital bills when she becomes sick. So that the Kafala system falls. So that it becomes a safe, kind country for all women. I protest because I despise living here, and I do not want to invest more effort and exhaustion in making another home in another country.

Palestinian woman, saboteur, infiltrator, maybe this writing will return to harm me, but my Palestinian comrades and I are a part of the fabric of opposition on the streets. We don’t want to repeat the mistakes of previous Palestinian leadership by lining up behind dictatorships and its funding, we don’t want to remain in the shadow of the Civil War, and we don’t want to feel the imposed alienation in the country of our birth and where we live amidst its changes. We are proud of movements like Tal3at (“women coming out”), and the discourse that views confronting patriarchy an essential part of confronting colonialism, and today we are coming out to confront the exclusion, discrimination, and institutional marginalization of refugees and migrants for the cause of global, human liberation. We refuse to be played like a card that invalidates the people’s demands, or a sign of failure, treason, or terrorizing, to distract from the righteousness of these demands. If you wanted to inject poison into news headlines by mentioning that refugees are behind this movement, then shame on those who could not find in that a testimony of virtue.

Palestinians in the Street: Our Concern, Not our Concern, by Sarah Kaddoura. Translated by David Kanj. Read the Arabic article here (& back-up link here).

Notes:

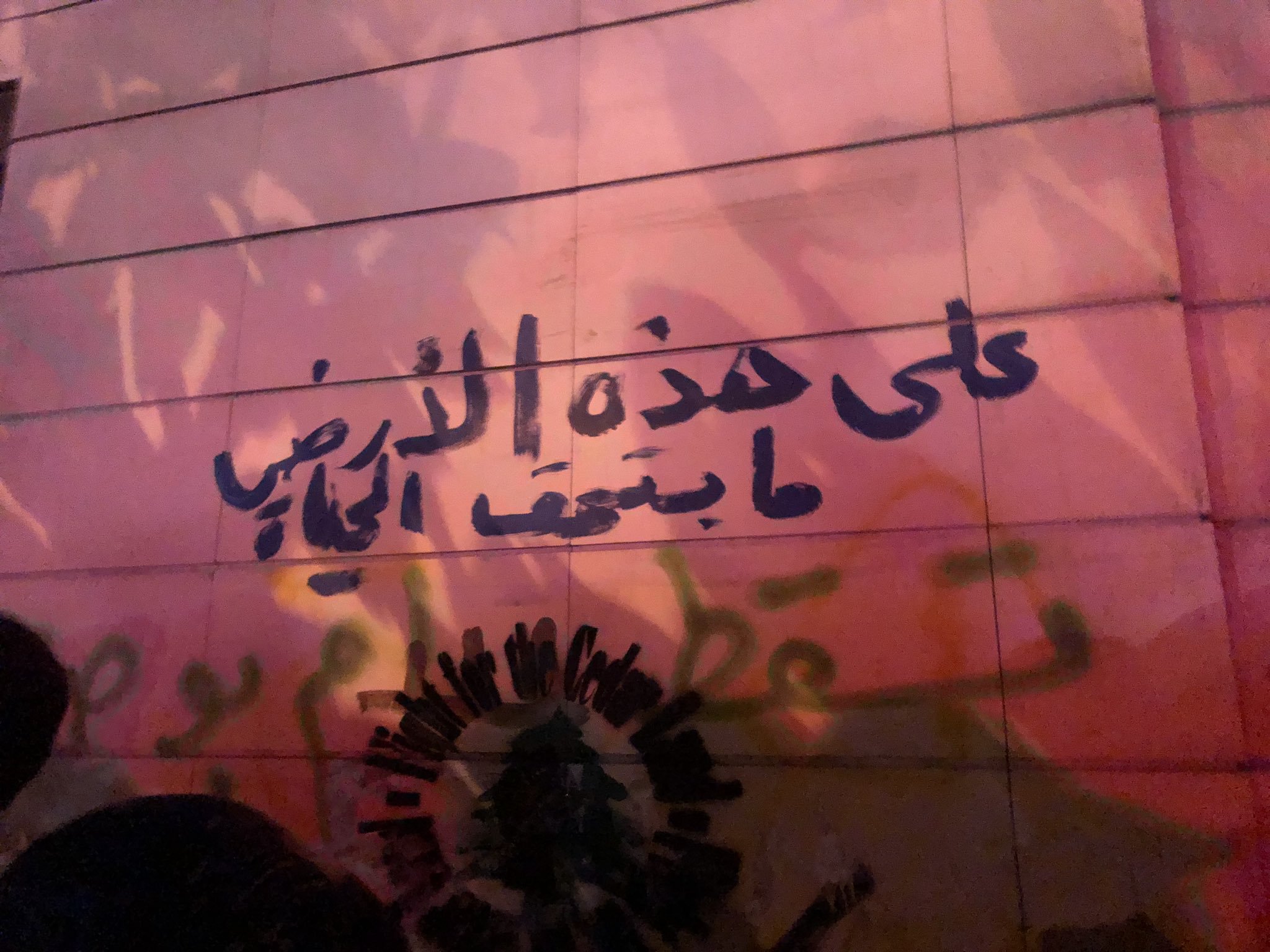

* Photo from a street in Beirut on 10/21/2019. “We Have On This Earth What Makes Life Worth Living,” from a poem by Mahmoud Darwish.

* The article is written in Modern Standard Arabic but with small bits of Levantine Arabic. If you are trying to read this but only know MSA, your best bet is the Living Arabic Project’s Levantine dictionary.

* Arabic has only two grammatical genders, masculine and feminine. While the masculine is traditionally used as the default/gender-neutral, the author uses the feminine gender instead, hence why I translate most instances of فلسطينيات, for example, as Palestinians rather than Palestinian women.

1: Rest House Tyr Hotel & Resort, owned by Randa Berri, was burned by protestors for its theft and privatization of the beach. An example of the news headlines can be found here.